15 min read

Seeing magic in the moonless night sky; How can Aboriginal pedagogy transform relationships to serve post-anthropocentric beings?

Key Terms

Womindjeka. I come with purpose for you, for us, for our environment and our totems (Steel, 2020)

Yarn means dialogue, meeting or discussion, (Yunkaporta, 2009; Steel, 2020). Yarns are used in the aboriginal culture to bind together, encourage diversity, and learn.

Posthuman “the posthuman predicament is the convergence, across the spectrum of cognitive capitalism, of posthumanism on the one hand and post-anthropocentrism on the other. The former focuses on the critique of the humanist ideal of ‘Man’ as the allegedly universal measure of all things, while the latter criticizes species hierarchy and human exceptionalism” (Braidotti, 2018).

Wicked problems are complex problems that offer consequences rather than solutions. Wicked problems are a consequence of the Anthropocene and are considered unsolvable. An obvious example of a wicked problem is climate change.

Deep Ecology, a philosophy of the interconnectedness of living and nonliving things. The biome in our stomach is reliant on a human being as is the human on her gut biome.

I celebrate the Wurundjeri people as enduring custodians of the land where this paper was written. I extend my gratitude to the Boon Wurrung, Anangu, Bunuba and GunnaiKurnai peoples who have shown unmeasurable generosity in sharing their knowledge and stories with me. I intend for this work to contribute towards bridging between our cultures. Acknowledging past injustice and to walk together into a shared and mutually acceptable future. No matter the length of our journey, I hope coalescing will heal wounds and reconstruct what it means to be Australian.

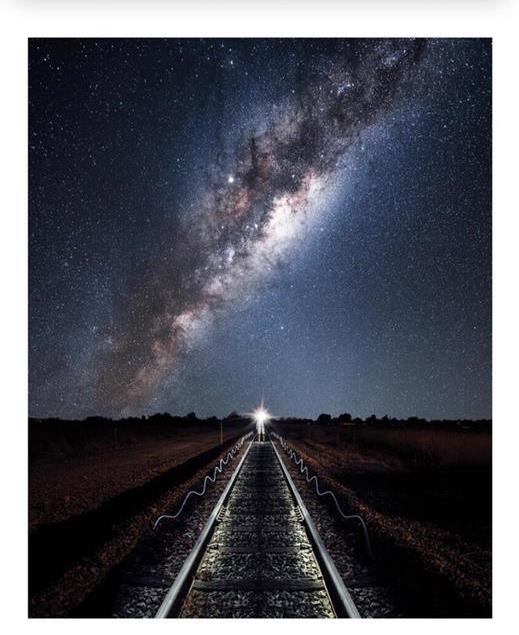

Full steam ahead (Pickering, 2020).

Wominjeka. I come with intent for you. To share through storytelling my transitioning colonial perspective as I learn about an ancient culture(s) and their precious lessons for our modern world. For us, by sharing stories we will transform our understanding of being. We might choose to learn toward sustainability. By investing in this research, we seek to gain insight, connecting cultures, our environment, spirituality, and healthy future.

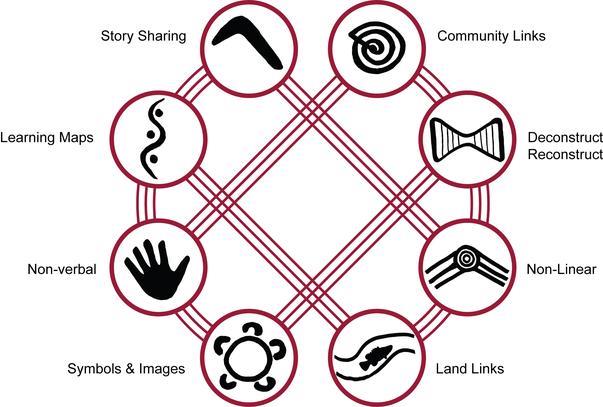

A research problem yarn

Whilst researching for this paper on appropriate epistemology and ontology for the post Anthropocene, I was presented with multiple paradigms in relation to academic writing. I have decided to move away from the dominant toward an indigenous model. This paper will meander in an attempt to embrace the Indigenous knowledge systems through the 8 ways framework (Nakata, 2007; Yunkaporta, 2009; Yunkaporta and McGinty, 2009). How does this style empower the reader to journey with an idea? How does it affect your relationship with the knowledge presented? As a white Australian, I am trained to work in straight lines. Full steam ahead! By meandering through nonlinear storytelling (Yunkaporta, 2009) and the inevitable deconstruction (Yunkaporta, 2009) of my own prejudice, I have found a different relationship with knowledge, much like turning off the light, one that resonates with some very western concepts advocating the rethinking of our ontology as we work toward a healthy future (Postman and Weingartner, 1971; Dewey, 1986; Delors, 1998; Zhao, 2005; Wals, 2011; Abram, 2017; Morton, 2018; Braidotti, 2019). We’ll get to that later.

We have begun this paper with the concept of yarning (Yunkaporta, 2019, 2019). This yarn involves nonlinear storytelling demonstrating a cultural gap. This review connects to a problem that our institutions are branding on those who emerge. Namely a relationship with knowledge causing debilitating effects when students are faced with the inevitable uncertainty and doubt. As I follow my torchlight the mysteries of the surrounding darkness weigh on my conscience. I continue. I feel on edge, uncomfortable.

Figure 1: 8 ways pedagogy (Yunkaporta, 2009)

I am in Gippsland Australia; I am a white male and in my 40’s. There is nothing to fear... Yet somehow, I feel surrounded by uncomfortable thoughts. I walk down the steep sand dune, onto the long stretch of ocean beach, I am surrounded by darkness. My torch frames my perspective I think I can see. Yet....

Now I am lying on the beach. My torch is off. The new moon gives little light. I am surrounded by cosmos. The Milky Way. Strangely, without the torchlight I see more. Profoundly more. And those feelings of anxiety have gone, replaced by awe and wonder. Turn off the torch I expect to see less. In reality I see more, and I feel much more at ease. I am looking up at history, at ancient light. I feel alive and curious.

I orient myself using the Southern cross. A box in the sky. A European consolation that works in straight lines. Much like the train tracks I am using the pointers and the cross itself allow me to generate a firm fix of my bearings. I am feeling more connected to this place.

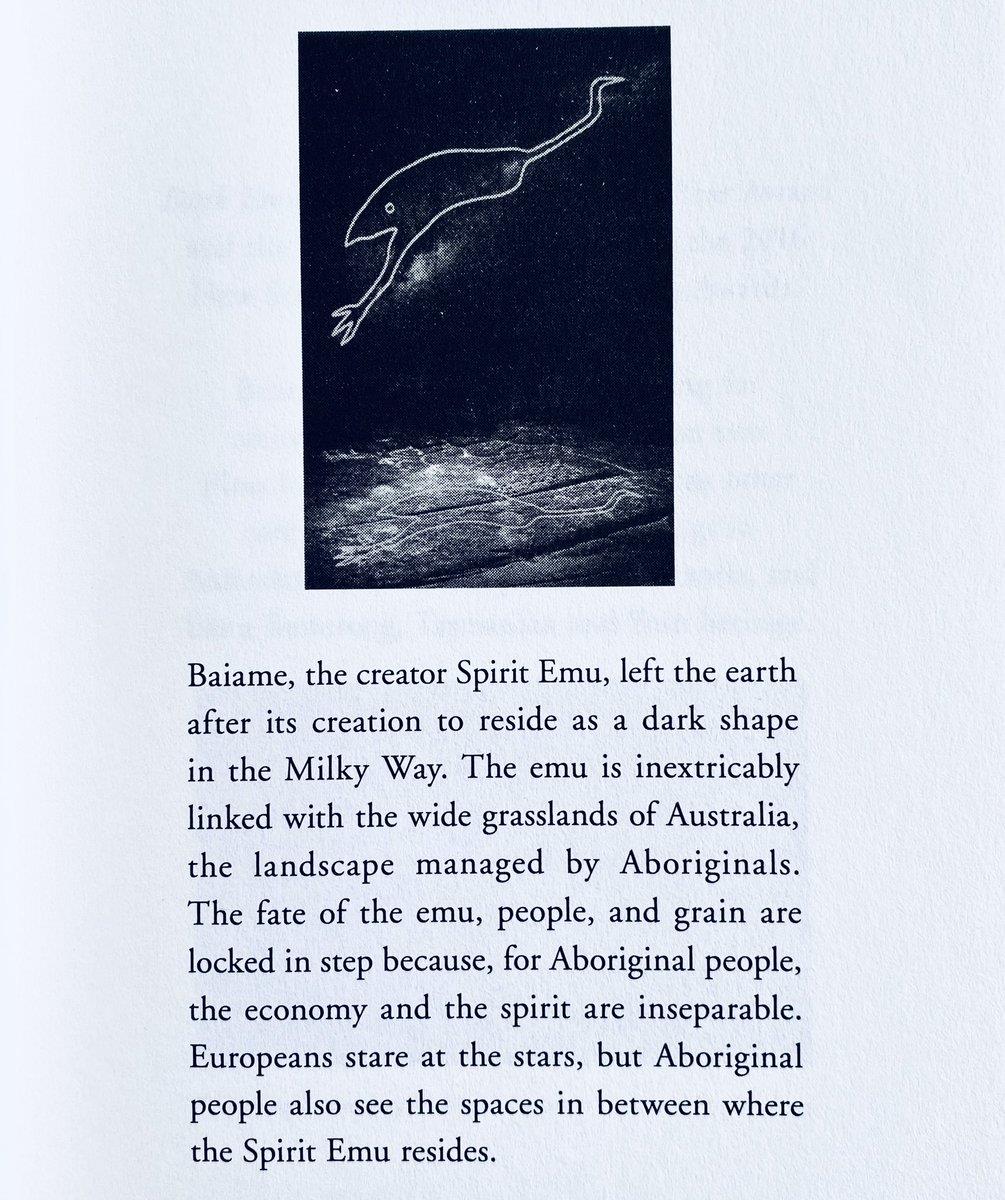

Aboriginal cosmology looks very different to my familiar European consolations. Like turning out the light and seeing profoundly more, Indigenous constellations use the gaps in the cosmos. Utilising nonlinear and darkness. The emu stretches across the Southern night sky like an artistic masterpiece. Its head is situated amid the square Southern Cross. Its neck and body trail out across the sky filling the darkness around the Scorpio consolation. Its legs continue off toward the other horizon. It is massive, majestic, and wonderful. From where I lie, there appears a significantly deeper and mysterious energy in the emu. It makes me think.

Purpose of the study yarn

The uneasy feeling the darkness beyond the torch light creates might represent the lived experience of high school graduates. The anxiety offered by neoliberal dualist thinking is at odds with predictions of chaotic climatic factors predicted as we continue to cook the atmosphere. Lucy Perso, a year 11 student shines light on this anxiety articulately.

“The kind of learning, where you’re given questions and there’s right and wrong, it sets you up for failure. There are so many ways to get it wrong and only one right answer.” Lucy Perso Maffra secondary college (Cook, 2018).

With leading western thinkers such as Einstein, advocating for a complex and interrelated world, the possibility of neo-liberal narratives being a problematic human construct is evident. Contrast this with interpretations of the night sky. Two cultures, two interpretations of the same sky yielding very different emotional reactions. Braidotti (2019) posits that being at ease with multi-dimensional complexity is essential for feeling at home in the 21st century.

Similar philosophies are echoed in the educational literature. An increasingly interconnected world demands of educators a dynamic and future focused education (Dewey, 1986; Delors, 1998; Zhao, 2005; Wals, 2011; Abram, 2017; Morton, 2018). Vast amounts of ever evolving knowledge are accessible at the click of a button or swipe of a finger. Timothy Morton’s work on ecological thinking shows another western perspective on the complexities and interconnectedness of the world. Perhaps the emu fig 2. might provide a symbol of another way to know, one that can help us overcome the complex challenges the Anthropocene creates.

Figure 2: The emu and southern cross in the nights sky (Pascoe, 2018)

Influencing change and increasing complexity are the focus of many educational philosophers. For the purpose of this narrative, I will use a broad definition of education outside of the walls of formal institutions; Postman and Weingartner (1971), Dewey (1986), Gilman et al (1989), Delors (1998), Zhao (2005), Wals (2011), Morton (2018), Braidotti (2019), Engelmann (2019) and Yunkaporta (2019) describe complexity as a reality of life. Moreover, realities inflicted by the Anthropocene on the more-than- human-world are not being adequately considered by the status quo (Abram, 2017; Morton, 2018; Braidotti, 2019). These accepted theses reflect in their argument striking similarity to Indigenous pedagogy. In his book Sand Talk, Yunkaporta (2019) posits a key difference Indigenous thinking offers in its communication and curation of complexity. This position encourages empathy and connection to the nonhuman and more-than-human-world (Abram, 2017; Morton, 2018; Yunkaporta, 2019).

Braidotti (2019) defined posthuman knowledge as the convergence of the two conflicting forces of neoliberal capitalist and post-anthropocentric forces. World changing effects, such as our changing climate system, as a result of human activity defined as the Anthropocene, have given urgent currency to the posthuman thesis (Braidotti, 2016). Through osmosis posthuman relevance has strong implications for educators as we are mandated to prepare our youth for their future. For the Boon-Wurrung, knowledge held by the elders transcends through culture a capability of the emerging citizens (Steel, 2020). Malone (2016) and Abram (2017) connect a similar philosophy to posthumanism, advocating for bridging the nature-culture divide and rejecting universalisms in favour of place consisting of multiple ecologies both human and non-human.

Education is rooted in the present with a view to the future. The present as both what we are ceasing to be and what we are in the process of becoming (Gilman et al., 1989; Braidotti, 2018). Given what we anticipate in the post Anthropocene, this knowledge must form a prism through which posthuman knowledge becomes explicitly relevant in modern education. Posthuman knowledge provides an ethical praxis that seeks to construct relative collaborative meaning that understands difference as a benefit to community (Santos, 2020). Posthuman knowledge therefore provides a case for learning past the dualism of the neoliberal. Linkage from posthuman to aboriginal pedagogy and deep ecology is provided by Rosi Bradotti (2019): “Unless one is at ease with multi-dimensional complexity, one cannot feel at home in the 21st century”.

Furthermore Morton (2018) shows the necessity for uncertainty if we are to embrace ecological thinking. Pink Floyd performs around a similar theme. “All you touch and all you see is all your life will ever be” (Waters, 1973). It is clear that all we know and the way we know it are actively creating the reality of posthuman knowledge.

Paradoxically students like Lucy Perso, have been struggling under the burden of dualist neoliberalism. What they know is leading to a debilitating being. Spannring (2019) links the consequences of dominant neoliberal structures as inhibiting ownership of subjective experience, inhibiting a caring and liberating relationship to the world. Morton’s uncertainty may then be well placed. Perhaps curiosity is a synonym for this state of being.

Harmonising with nature in order to thrive on this planet requires social transformation and life, in all contexts, affirming behaviours (Molina-Motos, 2019). Engelmann (2019) suggests we are all part of nature. If this mindset is accepted the instant realignment orients ourselves at one with a nature that is inherently dynamic and in constant change. “Abstraction and mysticism, deep ecology entails a valuable pedagogical dimension by bringing the responsibility of ecological change to the field of the conscience of the person” (Molina-Motos 2019).

Different cultures have different ways of being a student (Morton, 2018). Complexity is central to indigenous thinking (Yunkaporta, 2019). Dewey (1986), Delors (1998), Zhao (2005), Nakata (2007), Abram (2017) Morton (2018), Braidotti (2019) and Engelmann (2019) posit the importance of preparing ourselves for a dynamic and uncertain future realised by our Anthropocentric context. Yunkaporta and McGinty (2009) outline the following six areas that aboriginal knowledge might support: Knowledge, Problematic Knowledge, Higher Order Thinking, Student Background Knowledge, Substantive Communication and Knowledge Integration. Buxton (2018) reinfuses the possibilities of coalescing to meet the needs of post anthropocentric being by advocating for the collaboration and mutual benefit of Aboriginal ways of knowing because of their complexity.

Conclusion

Post anthropocentrism has realized a disconnect between current capitalist habits and needs and the environment we inhabit on Earth. Fuelled by neoliberal capitalist forces, educational systems have created a culture advocating for dualistic thinking. This reality places graduates, faced with uncertainties such as climate change, COVID-19 pandemic and jostling global political powers, feeling lost and powerless. Posthuman knowledge aims to turn pain and anxiety into action for all human and non-human. Echoing this aspiration, UNESCO calls for education to accept the constant and expected change and prepare students accordingly. Aboriginal Pedagogy appears well tested and well placed to provide the vehicle to bridge the gap developing students’ relationship with knowledge to both suit their present challenges whilst providing an ontology favourable to a healthy and thriving world into the future. Given the mutual significance our greatest challenge may also serve the overdue need to unite and reconcile our history.

REFERENCES

Abram, D. 2017, ‘THE SPELL OF THE SENSUOUS’, CSPA Quarterly. Center for Sustainable Practice in the Arts, (17), pp. 22–24.

Braidotti, R. 2018, ‘A Theoretical Framework for the Critical Posthumanities’, Theory, Culture and Society, 36(6), pp. 31–61. doi: 10.1177/0263276418771486.

Braidotti, R. (2019) Posthuman Knowledge. John Wiley & Sons.

Braidotti, R. 2016, ‘Posthuman Critical Theory’, in D. Banerji and M.R. Paranjape (eds_

Critical Posthumanism, Springer, India 2016 pp. 13–31.

Buxton, L. 2018, ‘Aboriginal ways of seeing and being: informing professional learning for Australian teachers’, AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples. SAGE Publications Ltd, 14(2), pp. 121–129. doi: 10.1177/1177180118764124.

Cook, M. 2018, Talkin’ bout a revolution. | Gippslandia. 17/10/2018

Delors, J. 1998, Learning: The Treasure Within, Report to UNESCO of the International Commission Pocket Edition. UNESCO.

Dewey, J. 1986, ‘Experience and Education’, The Educational Forum. Routledge, 50(3),

pp. 241–252. doi: 10.1080/00131728609335764.

Engelmann, S. 2019 ‘Kindred Spirits: Learning to Love Nature the Posthuman Way’, Journal of Philosophy of Education. Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 53(3), pp. 503–517. doi: 10.1111/1467-9752.12379.

Gilman, S. L. et al. 1989, ‘A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia’, Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 19(4), p. 657. doi: 10.2307/203963.

Malone, K. 2016, ‘Reconsidering Children’s Encounters with Nature and Place Using Posthumanism’, Australian Journal of Environmental Education, 32(1), pp. 42–56. doi: 10.1017/aee.2015.48.

Molina-Motos, D. 2019, ‘Ecophilosophical principles for an ecocentric environmental education’, Education Sciences, 9(1). doi: 10.3390/educsci9010037.

Morton, T. 2018, Being Ecological. 1st edn. uk: penguin random house. Available at: https://mitpress.mit.edu/books... (Accessed: 20 August 2020).

Nakata, M. 2007 ‘the Cultural Interface’, Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 36(S1), pp. 7–14. doi: 10.1017/S1326011100004646.

Pascoe, B. 2018, Dark Emu: Aboriginal Australia and the Birth of Agriculture, New Edition. Magabala Books.

Pickering, L. 2020, 'Full Steam Ahead', El Picko photography. Personal collection Viewed 15 August 2020

Postman, P. N. and Weingartner, C. 1971, Teaching as a subversive activity. Delta.

Santos, S. 2020, ‘Review of Posthuman Knowledge’, Journal of Posthuman Studies. Penn State University Press, 4(1), pp. 107–112. doi: 10.5325/jpoststud.4.1.0107.

Spannring, R. 2019, ‘Ecological citizenship education and the consumption of animal subjectivity’, Education Sciences, 9(1). doi: 10.3390/educsci9010041.

Steel, G. 2020, Yarn about Country: Gheran Yarraman Steel (VIC). Retrieved 15 August, https://www.youtube.com/watch?....

Wals, A. 2011, ‘Learning Our Way to Sustainability -’, Sage, 5(2), pp. 177–186. Waters, R. 1973, ‘breathe"- Pink Floyd.

Yunkaporta, T. 2009, Aboriginal pedagogies at the cultural interface. pdoc. James Cook University. Available at: https://researchonline.jcu.edu... (Accessed: 20 August 2020).

Yunkaporta, T. 2019, Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World. Text Publishing.

Yunkaporta, T. and McGinty, S. 2009, ‘Reclaiming aboriginal knowledge at the cultural interface’, Australian Educational Researcher, 36(2), pp. 55–72. doi: 10.1007/BF03216899.

Zhao, Z. N.- 2005, ‘Four “Pillars of Learning” for the Reorientation and Reorganization of Curriculum:’, p. 9.